Communication has been a hallmark of existence since the beginning of life itself (almost). Single cells communicate with each other through chemicals, ants communicate with pheromones, bees communicate through dance, and a variety of animals communicate through song/speech (see: birds, dolphins, doggos, etc.). Humans communicate through all of these media and more (except pheromones, we don’t really seem to have those, though research is ongoing). Recently, communication has been augmented by the internet, and even further by social media. Unfortunately, much communication through these means tends to be aggressive, offensive, and demeaning; it can be hard to have a positive experience online if you haven’t made an effort to make it so.

In such a negative atmosphere, my thoughts have often turned to issues of speech and expression, offense and apology. While it would be impossible to remember, much less document, all my thoughts, one of the questions that has stuck with me is as follows:

Is the reaction/response/impact of a statement the responsibility of the speaker or the audience?

On one hand, saying the speaker isn’t at all responsible flies in the face of everything we know about rhetoric and speech (and every experience we’ve had feeling inspired by what someone has said). On the other hand, saying the speaker is completely responsible also seems wrong, given that blatantly rude or offensive remarks can sometimes have no effect on the recipient. (xkcd has good examples of this dilemma here and here.) So what’s the balance?

This leads to a reformulation of my previous question:

To what extent is the reaction/response/impact of a statement the responsibility of the hearer and to what extent is it that of the speaker?

Recently Jeffery Holland gave a speech at BYU that has become a spark point for seemingly endless conflict and debate.

The topic: complicated.

The response: even more so.

(I would recommend reading the transcript here if you’d like a better idea of the issues.)

Many in the LGBTQ+ community and plenty outside it have decried Elder Holland, proclaiming the talk to be offensive, damaging, and painful, with some more extreme people calling Elder Holland a homophobe, a disgrace, or worse, and calling for his resignation.

Many in the LGBTQ+ community and plenty outside it have defended Elder Holland, proclaiming the talk to be a strong, albeit difficult, defense of church principles and a necessary call to arms, with some more extreme people (like this idiot) defacing public expressions of love and support and others suggesting actual violence.

Clearly there has been lots of room for interpretation.

So what do we make of this? Who is right? (Or is that even a valuable question to ask?)

I don’t know the answers to these questions. People who know a lot more than I do have written volumes on this topic, and probably have much better thoughts, but here are mine anyway (mostly in the form of more questions that I still don’t have the answers to).

Intent

Any analysis of speech or writing is incomplete if it doesn’t examine the author’s intent. Many people say the author’s intent doesn’t matter if the consequences are negative. In some ways this is true: if an engineer builds a bridge that falls down, it doesn’t matter if the intent wasn’t for the bridge to fall down. It happened, and the people that were hurt must be helped. So it is with speech: even if we didn’t intend to offend, our words can sometimes cause harm, and we must be willing to help all those who are hurt, even if we don’t understand or share such sentiments.

(Such unintentional offense does not make the speaker a malicious or even an incompetent person (despite some people’s insistence otherwise). Offense should be avoided wherever possible; latitude should be given when dealing with honest mistakes.)

This is complicated by the existence of some who would be offended no matter the logic, reasoning, or intent behind a speech. To extend my previous metaphor: if someone burns a bridge down, the engineer isn’t to blame, even if people are still hurt and it’s still the engineer’s bridge. Likewise, speech that is intentionally misunderstood or misinterpreted in order to claim offense is no longer the responsibility of the speaker.

This is where we find our first major grey area: how can we possibly know when someone is choosing to be offended rather than genuinely feeling offended?

In the same vein, how can we possibly know when someone is trying to be offensive rather than just making an honest mistake?

While these can be very difficult questions to answer, there are some principles that can help guide us. The most basic is this: Always give the benefit of the doubt. Rather than assume someone is a liar or that another is a bigot, we should treat them as if they truly have been hurt, or as if they truly have made a mistake. The worst that could happen if we’re wrong is that we’ve acted like civil people (a real hardship for some, even though this should be our standard of behavior anyway).

Some are tempted to say, “Well what about those instances when someone is so obviously being insincere/bigoted?” This is a reasonable question, until we realize that such thoughts only introduce another inscrutable grey area: How do we define what is obvious and what is not? Such subjective measures only lead to more disagreement, and it is best to give everybody the benefit of the doubt until more data can be gathered.

With our judgement withheld for the moment, the next step is to try to correct any possible misunderstandings. If we think a misunderstanding has occurred, on either side of the argument, we must begin what the ancients called “having a civil discussion.” This lost art form consists of objectively presenting evidence for your side, and then listening while the other side presents their own evidence. Comparison is made, evidence is weighed, and hopefully everyone has learned something new and seen a new perspective. If someone is persuaded to the other side, bully for them. If not, we get to our final point: disagreement is not grounds for incivility, harassment, or dickishness.

If we ourselves haven’t been offended, it doesn’t mean those who have are triggered snowflakes. On the flip side, if we have been offended, it does not mean everyone who doesn’t share in our offense (or understand it), is automatically an immoral bigot. Ricky Gervais said: “just because you are offended, doesn’t mean you are right.” This applies to all parts of the political spectrum.

In summary: It is the responsibility of the speaker to be as clear and precise in their speech as possible, but it is also the responsibility of the audience to try as hard as possible to correctly interpret and understand said speech. If offense is taken, offended parties should always be helped and heard. They should also always make a diligent, honest effort to ensure misunderstanding has not taken place. If an affected person makes a judgement about a person or speech without such effort, they are being unfair to the speaker. If an unaffected person disparages, discounts, or disregards the experience of an affected person, they are being unfair to that person.

Context

The context of a speech is crucial for a proper interpretation of it. Unawareness of the bombing of pearl harbor makes FDR’s “Day of Infamy” speech far less impactful. Unawareness of the history of slavery and racism in the U.S. does much the same to MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech. To properly understand any speech, we must study the context around it.

This context includes not only the historical events relevant to a speech, but also the culture in which the speaker lived. One of the most pervasive injustices we commit is judging the words, actions, and attitudes of historical figures based on our own cultural circumstances.

Similarly, to properly quote any speech we must also include the context around it. One of the most blatant forms of dishonesty is taking a quote out of context, yet this seems like one of the most common argumentative methods in use. Omitting such context is not only dishonest but also damaging: COVID misinformation is often spread because of contextual scarcity, and offense is often given or exacerbated for the same reason.

This brings us to another grey area: What context is important? How do we decide how much is “enough” context?

To this last one I can only say, if the meaning of a passage is so obviously distorted as to be unrecognizable, we need more context. But this just leads to more questions: How do we decide when the meaning has been distorted at all? Is any distortion too much, or is there an acceptable level? (It also leads back to “how do we define what is ‘obvious’?”)

Miscellaneous

To finish this long, winding, longwinded exposé, I’ve decided to include some of the other questions I’ve been pondering but don’t have a solid answer to. I’ll still include my preliminary thoughts, but if you have any input, I’d love to hear it.

1) Why is it “ok” to make fun of certain groups (flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, rich people, etc.) but not others (poor people, some religions, some races, etc.)? Is it because of a history of oppression? Or because some groups have consciously chosen to be part of those groups while others have no choice? (i.e. flat-earthers choose to believe those things, while people can’t choose their race or ethnicity.)

2) Why is it that some people are unaffected by blatantly offensive remarks, while others are offended by arguably harmless ones? Is it simply a matter of internal fortitude, or of previous experience?

3) Does offense given/taken by one’s position on an issue necessitate an apology by the one who holds it? Is it fair to be offended by internal beliefs? (I’m not talking about “I believe you are an idiot” kind of beliefs, but rather moral and/or religious ones.) Perhaps if those beliefs or positions lead to damaging or offensive behavior (or behavior that is perceived to be such)?

Conclusion

The art of communication is hardly as simple as the old clichés suggest, yet it remains one of the foundations of human existence. It is fraught with hazard, but rewards greatly the one who can master it (if such mastery is truly possible). We should always strive to perfect our communications, but what do we do in the meantime, as we discuss, dissent, and dispute imperfectly with imperfect people? The only definitive answer I can offer is itself a cliché, simple in principle and difficult in practice but powerful in application: be more kind.

Unnecessary Postscript

If after all this you’re still unsatisfied and want my specific thoughts on Elder Holland’s aforementioned talk, look here.

If not, feel free to ignore this.

Category: Uncategorized

A Quarter After

In my previous post I examined the Franklinism “Time is money”, exploring the idea that time and money are not one and the same, but rather each a form of currency. While time and money may be two of the most obvious forms of currency, they are by no means the only ones. In this post I’d like to talk about some other forms of currency, and why they’re important.

In addition to time and money, the currencies of life include energy, attention, and reputation. This is not an exhaustive list, and there are sure to be more, but these come to mind as the most common (I would love to hear about any more you might think of. A good way to tell if something is currency is to examine the way we talk about it. For example, we spend money, invest time, save energy, and pay attention. All are verbs we use when speaking of currency). Each currency has its time and place, but in their respective realms each currency is irreplaceable.

Energy

Energy is the currency of action. It is through exertion that we achieve our goals, whether working towards those things that bring happiness or to attain those that bring pleasure. The mastery of a skill requires not only time, but also energy. So does building loving relationships. Those who take time but exert no energy cease to progress, while those that exert energy but take no time start many things but finish none. When we lack either, we fail in our endeavor and frustration is our only reward.

Unlike time (and like money), energy can be saved, allowing us to use it later in other pursuits. This can be done in two ways: First, by doing nothing (ok not nothing, but I think you know what I mean). Doing nothing is an excellent way to save energy (it is also an excellent way to waste time). Second, by increasing efficiency. When we do something more efficiently, we take less time and energy to accomplish the same task, giving ourselves more time and energy for other pursuits. Science and commerce have increased the efficiency of almost everything: getting food is a matter of going to the store and buying it (or stealing it) rather than living on a farm and raising, growing, and harvesting it yourself. Travelling long distances is a matter of hopping in your plane, train, or automobile and going 700 miles in a day rather than 70 in a week. This increased efficiency has given us more energy and more time; now the challenge is to use that time and energy in worthwhile pursuits rather than basking in the ennui of post-modern life.

Attention

Attention is far less obvious as a currency, but it is as pervasive as time and as powerful as energy. Every waking moment we spend the currency of attention: on Facebook, TikTok, our families, the news, video games. The list is literally endless. Attention has become a multi-billion dollar industry, with every restaurant, clothing store, website, app, and business trying to steal your attention. If we aren’t careful (if we don’t act with intention), we can spend our whole lives paying attention to things of lesser value while those things of import go, if not unnoticed, unattended.

On the other hand, attention well-spent leads us to great heights. We learn by attending to good books and good music, or by attending class; we develop spiritually by paying attention to our spiritual leaders or holy writings; and we improve mentally and emotionally by paying attention to our thoughts and feelings and understanding how they contribute to our well-being. Much like time and energy, developing relationships and skills requires our attention. In fact, the trifecta of time, attention, and energy is one of the most important combinations of resources we have. They are the vital ingredients for success in any undertaking.

Reputation

Reputation is perhaps the least obvious of currencies, but it is nonetheless significant. We build our reputations among those around us one decision at a time. We gain a good reputation when we act admirably, serve others, do good work, or keep our word. We gain a bad reputation when we act selfishly, put others down, shirk our responsibilities, or break our promises.

Reputation is unique among currencies in that it is not spent and saved the way others are. Reputation doesn’t necessarily diminish when we use it to improve and progress. For example, a woman of high reputation is able to use her standing to secure better employment, or assistance for those she cares about without her reputation being tarnished. Conversely, we can throw away a reputation at the drop of a hat by acting contrary to the character we have cultivated: a person of high reputation can acquire great wealth and power while simultaneously destroying their reputation if such wealth and power was acquired immorally or unethically. In both instances the currency of reputation is used, but depending on how we act in relation to our established reputation, we can increase or decrease the purchasing power it affords.

Interestingly, reputation is also unique in that it, alone, passes with us beyond the grave. When life is over and we have spent all our time and energy, and when our money is no longer ours, we will long have our reputations. This may not seem like much to a dead person, but when we look at the number of hospitals, charities, humanitarian programs, and institutions of learning that have been named for and inspired by those that have passed before, we can see that reputation has perhaps the greatest potential of all as a powerful influence. The welfare of millions can be purchased with the reputation of just one.

Finally

With each of these currencies in mind, there is one last topic I’d like to discuss: exchange between currencies. Much like the exchange between time and money and vice versa, we make exchanges between all currencies. To name a few (among many others): we exchange time for energy when we sleep; we exchange time, energy, and sometimes money when we build our reputations; we exchange our money for energy when we buy more efficient tools and appliances; and we exchange our reputations for attention when we delegate tasks to or ask favors of others.

These exchanges underlie everything we do in life, and they cannot be done away with; we can’t go without sleep, and we build a reputation no matter what we do whether we like it or not. Sometimes the drive for more currency dominates our life and we do everything in our power to acquire money, or to gain fame and recognition, or to lie around sleeping all day. The thing is, a happy and successful life doesn’t come from the acquisition of currency (saving all the money in the world, having boundless energy, or building a towering reputation). It comes when we spend our currencies on those things that actually bring happiness and success: spending our time and energy creating loving relationships, using our money and reputations helping those in distress or poverty, or directing our attention to the people who feel unloved, uncared for, and unnoticed.

Having currency is what allows us to live our life, but spending currency well is what makes our life worth living.

Nickels and Times

Benjamin Franklin is often considered one of the most intelligent of the founding fathers of the United States. He was a great politician, taking part in the continental congress and serving as the first U.S. ambassador to France and Sweden; he was a great inventor and scientist, inventing electricity with a kite and influencing such fields as demographics and meteorology; and he was a great writer, helping draft the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence and publishing many other works on a variety of topics. (And a lot of other stuff too. He honestly was a smart dude).

Because of his wit and intelligence, many of Franklin’s works are still known today, and many of his aphorisms have gained ubiquitous recognition. In addition to keeping doctors away by throwing apples at them and saving and earning pennies, Franklin is also known for this little gem:

Time is money.

This maxim is almost universally known and respected (though few people know about the full quotation). Franklin continues:

He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that day, though he spends but sixpence during his diversion or idleness, it ought not to be reckoned the only expence; he hath really spent or thrown away five shillings besides.

Advice to a Young Tradesman, 1748

This concept has played an important part in modern society. It has become so prevalent that it is accepted almost without question, and has led to the publication of innumerable books, articles, magazines, and blog posts. In many ways this kind of thinking is useful and leads us to better utilize our time, or to be more wise with our money, but in reality it is not entirely true (sorry Benjamin Franklin).

Time (those discrete intervals (seconds, minutes, hours, etc.) we spend in various pursuits) is not money (those discrete quantities (dollars, cents, yen, dinars, etc.) we spend for goods and services). This isn’t to say time isn’t valuable (it clearly is), but it is misleading to say that one is the other. It doesn’t help that our vocabulary lends itself to this kind of thinking; the verbiage we use regarding time closely resembles that which we use regarding money: we steal moments and live on borrowed time. We find spare moments like we find spare change. We spend time and save it, waste time and invest it. Everything around us leads us to treat time and money as if they are the same. This kind of thinking, however, is fraught with danger.

Before we can understand why it is so dangerous, we must first understand the true relationship between time and money; it isn’t that time is money or money is time, it’s that both time and money are currency (defined in this sense as “something that is in circulation as a medium of exchange“). Money as currency is obvious: we spend money and we get food, housing, or heroin. Duh. We do it all the time (buy stuff I mean. We shouldn’t be doing heroin all the time). We have a harder time with time; it is a less obvious currency, though it, too, is exchanged daily. We spend time and we get education, entertainment, or sleep. Most of all, we give time and we get money, whether paid hourly or with a yearly salary. We spend our time making money and we spend our money on things that save us time.

This concept is dangerous because not all currencies are equal. Our global economies run on money, but the economy of love and the economy of life do not. We cannot purchase a happy family with money, nor can we master a skill just by being rich. No amount of stocks or bonds will ever rectify a ruined relationship with a family member or friend. These things require a different currency: not the currency of money, but the currency of time. This is what is meant when we say money can’t buy happiness, or as the Beatles said, “money can’t buy me love.” The price tag of happiness and the price tag of love are not written in dollars and cents, they are written in days, weeks, and years. They are written in the small moments we share with the people we love.

As Bruce Hafen said, “We give our lives, even an hour at a time, for what we believe, what we value, and whom we love.”

Money is still important; we can’t pretend like we don’t need it, and we shouldn’t turn away the poor and needy when they ask for it under the pretense that money won’t make them happy. But money should never become the focus of our lives. Time is far more valuable. The biggest difference between the two is that money can be saved, spent, or locked away, while time continues its inexorable march one second, one minute, one day at a time. It is relentless, irrepressible, unstoppable. It is spent whether we want it or not, and no amount of money can ever get it back.

What will you spend it on?

Tarot, Tweets, and Sacred Chickens

As 2020 came to an end and 2021 began, people around the globe looked forward to a new year, one that would hopefully be less terrible than that which just ended. Then, on January 6th, the U.S. capitol was attacked and overrun by so-called “patriots” and the hopeful spirit that always accompanies the new year was dashed in an instant. “2021 had a good run, here’s to 2022.” some said. Or, “Well, that was fun. Here’s to 2022.” Or a multitude of others all expressing the same sentiment: now that something bad has happened, it looks like 2021 is going to be another crappy year.

While most of these (hopefully) were said in jest, I can’t help but think some people really do feel that way; they think the swiftness with which misfortune struck in 2021 portends another year of unrelenting misfortune, and they have resigned themselves to whatever horrors the new year will bring (a truly cheery sentiment). For these people, I imagine 2021 really will be a rather terrible year.

The attack on the U.S. capitol was indeed a horrible event, but it was by no means oracular (that’d be like getting your fortune told by a redneck who looks at Trump’s Twitter and randomly chooses a tweet). The course of a year isn’t determined by it’s first days, and the import of a year can only be determined in its last ones. Until then it is full of potential, and we decide how and when that potential is realized.

In the Book of Mormon we read that there are things to act and there are things to be acted upon (2 Nephi 2:14). When we look at an event like the storming of the U.S. capitol and think “Well this year is going to suck,” We’re allowing ourselves to be acted upon rather than acting for ourselves. When we confidently start a new day and then let a 5-minute interaction with the worst person in the world (or maybe even just someone annoying) ruin the remaining hours, we’re allowing ourselves to be acted upon rather than acting for ourselves. Success is achieved only after we take control and become men and women of action.

One of the many interesting aspects of the ancient (and often modern) world is the veneration given to fortune-tellers, augurs, soothsayers, and oracles. Ancient Eurasian people developed palm reading, African peoples have used basket or metallurgical divination, and Ancient Greeks used several different forms of augury. Even today astrological symbols, crystal balls, and tarot cards are revered by many in western culture. While many of these traditions are religious (and I’m not here to disparage anyone’s religious beliefs), it seems many people use these practices as ways to absolve themselves of responsibility; they let the daily horoscope determine their life, or the fortune-teller down on main street, or the 10-day weather forecast. In perhaps one of the most delightful examples (and one I could see myself getting behind now), Ancient Romans would regularly consult the sacred chickens to determine the correct course of action.

Flippantly allowing external forces to determine the course and quality of life is foolishness (especially if that external force is a flock of chickens). Tragedies may transpire and disasters may deter, but to give up hope at the first sign of trouble is cowardice. Life is, undoubtedly, difficult, and some days we will be beaten and bruised, but still we must rise. We alone determine our course in life and our attitude toward it. Like William Ernest Henley, we are the masters of our fate and the captains of our soul.

2021 will only be a terrible year if you allow it to be. Today will only be a good day if you make it so. Take responsibility and take control. Don’t give into inertia. If you really want to know how your day, your week, your month, or even your year will go, ask yourself what you’re going to make of it. Otherwise, go talk to some chickens.

The 2020 Book Awards

Of all the things that have happened in 2020 (insert comment about any of the dozens of things that have happened, or about how horrible a year it’s been, or any of the other cliché topics that will be repeated millions of times in the coming days), not all of them have been relentlessly terrible. More of my friends have gotten married than I can keep track of, I was able to visit some cool places I’d never been before, and The Mandalorian season 2 was about as perfect as I could have hoped.

In addition, I made a goal near the beginning of the year, as the pandemic began to affect life in Utah, to use the time I would have in relative lockdown to read as many books as I could. This goal came from a mixture of my love of reading and my desire to not let myself use all my downtime playing video games or scrolling through Facebook. I’m glad I made it because 2020 has been a fruitful year for reading (it’s also been a fruitful year for playing video games and scrolling through Facebook…).

I read a wide range of books, including plays, biographies, autobiographies, fantasy, religion, philosophy, psychology, business, mathematics, history, and more. Some books were read because I’d seen the movie first and some were read because I wanted to be able to say I did. Some were read because I love the author and some were read because I love the subject matter. With such a wide sampling of books I thought it altogether fitting and proper to give out some awards for the books I read so that you, too, might be able to enjoy some of my reading (or at least know which books might be worth your time or not). Let’s get to it!

Awards

Best Fiction: Okay for Now by Gary Schmidt.

Shout out to Annemerie Jensen for suggesting this one. It was a fun, light read full of emotion and fabulous writing. I loved it. It also has the distinction of being the first book I read this year. 10/10

Runner-up: Persuasion by Jane Austen.

Very Jane Austen-y, and therefore very enjoyable. Shout out to Nick Versaci for encouraging me to read this one. 8/10

Best Autobiography: Surprised by Joy by C.S. Lewis

It helps that I really like C.S. Lewis, and also that I only read two autobiographies this year. But it was fascinating to get a look into the life of one of my favorite authors and to see what shaped his life and beliefs. It was a little hard sometimes because of so many place names, but that didn’t diminish my enthusiasm (it apparently did diminish my mom’s though, who barely finished it). 8/10

Runner-up: Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence

It helps that I only read two autobiographies this year. I didn’t actually like this one too much, which is a tragedy because the story is cool and there was so much potential. One of my favorite quotes of all time comes from this book, but it was overall a dud. Too many place and person names that I didn’t understand or follow, though still a fairly good look into Middle Eastern culture. 5/10

Most Inspiring: Love Does by Bob Goff

Shout out to Joseph Douglas for suggesting this one. This is one of those books that just gets you excited for life, and makes you want to go out and talk to strangers and do wild, spontaneous things in the name of living and loving. A real treasure of a book. 9.5/10

Runner-up: Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Often listed as one of the most-read and must-read books ever written, this book was definitely worth it. It was different than I expected, with a lot more biography, and then a lot more psychological analysis, which didn’t flood me with inspiration (but was still very good), but what it did have in that regard was great. 9/10

Runner-runner-up (runner-up-up?): Ragamuffin Gospel by Brennan Manning

I have to throw this in here. The only reason this book didn’t get an award is because I didn’t reread it in its entirety this year. If I had, this book would have clinched the win without question. Certainly in the top 5 books that has impacted my life. Highly recommend. 15/10

The Book Actually Wasn’t Better: Caging Skies by Christine Leunens

The inspiration for the movie Jojo Rabbit, which was incredible, this book was truly not great. I mean maybe it was for someone else, but for me this book was an interesting concept that started with promise and then ended in a weird, depressing sexual nightmare. Truly horrifying.

Book: 2/10 Movie: 10/10

Runner-up: My Abandonment by Peter Rock

I didn’t even watch the movie (Leave no Trace), but it looks pretty good (it also happens to have the same actress who starred in Jojo Rabbit). The book started alright, and the story is fascinating (based on a true story of a father and daughter living off the grid in the woods near Portland), but it then also turned into a weird existential nightmare.

Book: 4/10 Movie: ??/10

The Book and the Movie Were of Similar Quality: Wild Pork and Watercress by Barry Crump

The inspiration for the movie Hunt for the Wilderpeople, which was incredible, this book was also a really fun read. The movie is quite different than the book, so it’s not really fair to directly compare them, but I had a good time reading this book; It was a light, fun read about adventuring in the woods. I’m a fan.

Book: 9/10 Movie: 10/10

Runner-up: The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare

I didn’t even watch the movie (10 Things I Hate About You), but everyone keeps telling me I need to watch it, so I assume it’s good. Aside from the sexism, the book was also pretty good, with a lot of classic Shakespearean double entendre, innuendo, and punning, as well as some very confusing dialogue for me, the 21st century English speaker. I enjoyed it, though it wasn’t my favorite ever.

Book: 7/10 Movie: ??/10

My Reading Habits Would Suggest I’m Obsessed With This Author: C.S. Lewis

And my reading habits would be right. I love C.S. Lewis. His books are amazing, and I’ve loved pretty much every one I’ve read (except, oddly, The Screwtape Letters). My favorite so far: The Problem of Pain or The Weight of Glory. At this point I’ve read a significant portion of his more well-known books (except, oddly, Mere Christianity), and I own a significant number as well. He’s the man. 10/10

Runner-up: William Shakespeare

In this case my reading habits would be slightly wrong. I do enjoy Shakespeare, but I’m not obsessed with him. I decided this year that I should read more of the classics, so I read quite a few of his works (more of his comedies), but again, sometimes it’s hard to understand when I’m reading them from the 21st century. 8/10

Best Twist Ending: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

An engaging book that really made me think about decadence, hedonism, and the role of pleasure in life. The ending was also a roller-coaster (the good kind that I can handle). Obviously I don’t want to give it away, but it was a fabulous ending that left me satisfied. 7.5/10

Runner-up: None

I didn’t really read any other books with such a twist. I did reread The Life of Pi by Yann Martel, but I actually hate that ending, so it doesn’t get an award, except maybe the “Worst Twist Ending” award. But that’s just me.

Most Funniest: The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

While Shakespeare’s works can be quite comedic (Macbeth? Hilarious), The Importance of Being Earnest really took the cake on this one. Maybe it’s because it wasn’t written in the 15th century, and therefore the humor was far more accessible to me, but this book is a lot of fun. I realized the movie is also a lot of fun, and this probably also deserves the award for that, but it’s too late and I’m not changing it. But both the book and the movie are a blast. 9/10

Runner-up: Humble Pi: A Comedy of Maths Errors by Matt Parker

This could also have won the “Nerdiest” award, since it’s a book about maths, but one could argue that reading a bunch of books about a bunch of stuff and then writing an absurdly long post about it is itself extremely nerdy (and one would probably be right, but one could also shut one’s mouth). This book was an exposé about all the ways math has failed and things have gone either horribly wrong or just mildly wrong in the world, and why that’s funny. Sometimes it was hard to understand because math, but overall it was a fun read. Bonus points for fun covers. 7/10

Best Historical Work: Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World by Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan is one of those names everyone knows but no one knows much about. That’s where I was at before I read this book, and I wanted to know more about this hugely famous figure. This book did not disappoint, and neither did Genghis Khan. I learned so much not only about the man himself, where he came from, how he was able to rise to prominence, and why he was so successful in creating the largest empire in history, but also more about Asia than I ever expected (or knew there was to know, embarrassingly). I’ve had a very Euro-centric education, and this book changed nearly everything about my perceptions of Asian culture and influence, and I would highly recommend it to anyone in the same boat as me. Genghis Khan was the man. 10/10

Runner-up 1: The Bully Pulpit by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Shout out to my Uncle Reed for recommending this one. This also has the distinction of being the longest book I read this year (750 pages). All about Teddy Roosevelt, William Taft, and the world in which they made their mark, this book was a very detailed look into a very interesting time. Sometimes a little too detailed, but that also helped create a vivid atmosphere that immersed the reader. Overall great writing, and a great look into why Teddy Roosevelt is one of the most popular presidents (and people) in history. 8.5/10

Runner-up 2: Scipio Africanus: Rome’s Greatest General by Richard A Gabriel

There’s a second runner-up in this category because, even though this book was objectively not as well-written as The Bully Pulpit, I definitely enjoyed it and couldn’t let it be forgotten. As I’ve said before, I love Roman history, and this is actually one of my favorite eras of Roman history; Hannibal and Scipio are epic, almost mythical figures, and learning more about them and the events they participated in and caused was a really fun time for me.

Objectively: 7/10 Personally: 9/10

Most Thought-Provoking: The Rational Optimist by Matt Ridley

One of those books that challenges a lot of the preconceptions we have in society, this book is fascinating. It traces the rise of prosperity from the beginnings of human societies down to the present time, sharing why the pessimism and fatalism of the present day is unfounded, and why, in spite of the seeming rise in catastrophes and suffering in the world, we really do have reason to be optimistic and happy. The writing was engaging, and the concepts discussed and evidence presented were quite convincing. It really expanded my view and helped me see things through a different lens. 9/10

Runner-up: Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

This book was very engaging and similarly mind-expanding like The Rational Optimist. It explored the real roots and requirements for creativity, and how to develop and cultivate creativity in life. It also gave examples from the lives of some of the top creative peoples of the 1900’s in the form of interview transcripts and short biographies. It did wax a little long towards the end, but overall the book was very thought-provoking (obviously). 8.5/10

Favorite New Author: Ryan Holiday

It’s kind of a shame none of his books got any awards here, because I did really love his books. Ego is the Enemy, Stillness is the Key, and The Obstacle is the Way have been some of my favorites that I’ve read this year, and several of the other books I read this year (Genghis Khan, Creativity, and The Rational Optimist to name a few) came because they were referenced in one of those three books, so I owe Ryan Holiday. I loved the stoicism taught in his books, and the way he drew examples and evidence from people from all walks of life and in all time periods of history. They really are fabulous books, and he’s a fabulous author. 9.5/10

So there you have it, my 2020 reading list in review. Hopefully this didn’t bore you, and if you disagree with any ratings, or think I’m a huge idiot for my reviews, let me know!

To see a full list of books I read this year see here.

I Don’t Know, I’m Afraid

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

H.P. Lovecraft

“We fear things in proportion to our ignorance of them”

Christian Nestell Bovee

We humans, in spite of all our rhetoric about being logical, rational creatures, are constantly at the mercy of, or significantly affected by, our emotions. They affect how we respond to and interact with others, how we spend our time, what (or if) we eat, and nearly all other decisions we make. The stronger the emotion, the greater its effect in our life, and one of the strongest (and therefore most influential) emotions we experience is fear.

Fear, like all emotions, plays an interesting and complex role in our existence as biological organisms. Clearly it evolved for an important life-saving purpose: being afraid of snakes and spiders makes you less likely to get near one, and therefore less likely to die by being bitten. Being afraid of bears makes you less likely to fight one, making you less likely to get suplexed.

On the other hand, fear can be one of the most crippling emotions we experience. The fear of being judged, ridiculed, or humiliated prevents people from expressing themselves and opening to others. The fear of failure prevents people from starting new projects, exploring alternate career paths, or developing relationships. Fear of dogs prevents people from enjoying dogs. In each of these cases, fear limits the human experience and inhibits the satisfaction that comes from effort, accomplishment, and connection (and dogs).

So what exactly is fear?

It seems like a stupid question because, duh, everyone knows what fear is (except for those rare people who lack functional amygdalae), but if you really tried to answer it right now I imagine many of you would say, as I first did, something like: “it’s, uh… being afraid of something.”

Everyone knows what fear feels like, but not necessarily what it is. It’s one of those fundamental experiences that is hard to describe precisely because it’s fundamental (similar to describing what salt tastes like, or what blue looks like).

What fear is, however, differs from what it feels like, just as what blue is differs from how it is perceived.

So what exactly is fear?

While my thoughts may not be a complete (or even adequate) exploration into the nature of fear, they have changed my own perspective on fear, and how to deal with it more effectively. As I’ve thought about and experienced fear (and then thought about my experiences), I’ve come to three conclusions:

Conclusion One: Fear is Uncertainty

Fear is a predictive emotion. It is based on our analysis of the future, and what we think could happen, not necessarily on what will happen. We don’t fear the past or the present, because we know what they hold, but we do fear their possible impact on the future. And we fear the future because we don’t know it. Take, for example, a fear of flying: when someone is afraid of flying, what they’re actually afraid of (usually) is that the plane might crash, a possible, though perhaps not probable, outcome. Or perhaps someone fears heights: what they are really afraid of isn’t being up high, it’s the uncertainty of whether or not they will fall.

So it is with all fears: we fear the uncertainty of the future, and it’s innumerable possibilities.

(An important, perhaps obvious, note: The actual probabilities of an event occurring are not always directly proportional to the fear experienced; Rather, our perception of danger is what drives fear. Phobias and anxiety disorders are caused by a perception that is disproportionate to the actual probability of an event. This is the distinguishing factor between a healthy and an unhealthy fear: a healthy fear is one in which our perception of danger and our response to it are proportional to the actual danger and probability of an event. An unhealthy fear is one in which our perception and/or response are disproportionate to the actual danger present. This can go both ways, either as an overreaction to uncertainty or as an underreaction to uncertainty, though the latter is often, erroneously, called courage and as such is often, erroneously, encouraged.)

Corollary: When an outcome is certain to occur, we no longer fear it.

This may seem counterintuitive, but it’s true. When we know something is going to happen our fear shifts from the uncertainty of the event to the uncertainty of it’s outcome. When the uncertainty of an event is removed entirely, so too is our fear. Often what we consider to be fear is really an aversion to something (perhaps because it was associated with fear in the past). You can see this in any fear you have. For example, when I say I’m afraid of needles, what I really mean is that 1) I’m afraid what it would be like if a needle broke inside my arm and 2) that I actually hate them, because they hurt.

Or take my previous example of a plane crashing: if we are in a plane and we know with certainty it’s going to crash, we lose our fear of the plane crashing and instead begin to fear that being in a plane crash is going to be a horrible experience (which seems like perhaps a reasonable expectation). Interestingly, the whole reason we would experience the fear of a plane crash in the first place is because it leads naturally into our secondary fear of what a plane crash will be like. This leads me to my second conclusion.

Conclusion Two: Fear is Layered

Fears are like ogres, which, in turn, are like onions (or cakes or parfaits): they’re layered. Nearly every fear we have is built upon a different fear one layer below it, a fear that can be revealed by asking the question: Why?

For example: You’re afraid of the ocean. Why are you afraid of the ocean? Because you don’t know what you’ll encounter in it. Why are you afraid of what you might encounter? Because it might eat or sting or bite or drown you. Why are you afraid of being eaten, stung, bitten, or drowned? Well, hopefully that answer is rather obvious.

This exercise can be performed with any fear, often to great, enlightening effect. You may find fears you didn’t realize you had, or you might find that the things you thought you feared weren’t worth fearing. Whatever it is, remember: Fears rarely exist in isolation.

Eventually, however, you will reach a point at which asking “why?” doesn’t lead you any further. This leads to my third and final conclusion about fear.

Conclusion Three: Pain is the Root of Fear

When we follow any fear to it’s fundamental source, we arrive at pain. Pain is the root of all fear. If it isn’t painful, emotionally, mentally, or physically, we don’t fear it, even if it is full of uncertainty. This is what separates fear from excitement or anticipation: we are excited for pleasant uncertainties, but fear unpleasant ones.

This is not to say that any time we expect to experience pain or discomfort we experience fear, but rather any time fear is present it is because of pain or discomfort. Social anxiety is caused by fearing the pain of ostracism or loneliness. We fear the pain of rejection, the pain of shame, or the pain of living without a loved one. Whatever it is we fear, it is because we fear pain.

Conclusion

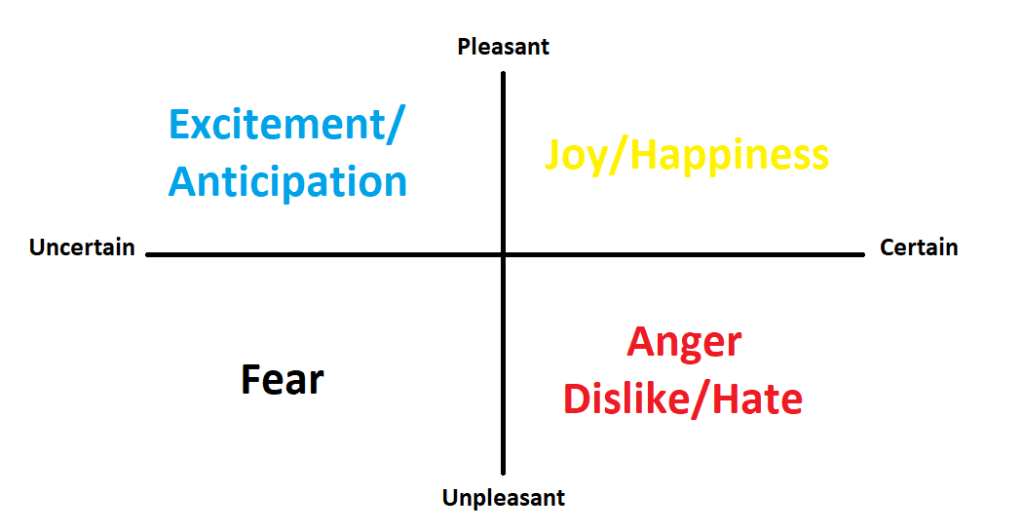

With these conclusions taken together, we arrive at our (partial) definition of fear: It is an unpleasant emotion we experience when faced with the possibility of pain. If it is not uncertain, it is dislike or hatred. If it is not painful, it is excitement or anticipation. If it is neither, then it’s enjoyment or happiness. This is illustrated in this very simplistic chart I’ve made (Obviously not every emotion is represented on this chart, like disgust or guilt or hunger, and often these emotions can blend with each other, but this serves my present purposes):

The first step to overcoming any obstacle is to understand what the obstacle is; “Know thy enemy”, as Sun Tzu admonished. With our improved understanding of what fear is, we are more prepared to learn how to overcome it. And as George Addair said: “Everything you’ve ever wanted is on the other side of fear.”

The Sufficient-est

Sufficient (adj.) – Enough; Adequate

An interesting word, fraught with cultural and linguistic dubiety: while its definition would suggest a certain amount of positivity or optimism, its connotation is often quite the opposite. To have your work described as sufficient is essentially an insult. To say “my [significant other] is sufficient” sounds almost comically terrible. And no one is ever promoted for being sufficient. Instead we must be the best, the brightest, the most attractive, the richest, or the most famous. Our society is driven by superlatives; to be sufficient is no longer sufficient.

This superlative drive pervades nearly every aspect of life: we have to have the best business idea and make the most money; we have to have the best grades and graduate first in our class; we have to have the most friends and followers; and we have to have the biggest house with the nicest yard. Politics, science, religion, academics, relationships, friendships, and more are dominated by the superlative drive.

I’m not saying the drive to be better is inherently bad; we strive for superlatives because superlatives are, well, super. Excellence in any positive aspect of life is an admirable quality, and many superlative people are well worth emulating. But when this healthy desire to be better warps into an obsession (as it generally has) it quickly leads to shame, guilt, and self-loathing. We begin to believe that any blemish, misstep, or failure disqualifies us from a happy, meaningful life. Even imperfect-yet-good performances are viewed negatively, deepening our feelings of inadequacy, just as we begin to show improvement and promise.

The thing is, the world doesn’t operate on superlatives (no matter how many beauty salons and ad agencies would have you believe otherwise). Jeff Bezos may be the richest man in the world, but to say he’s the only one living a good life is nonsense (many people would say he isn’t even doing that). it doesn’t take $175 billion to be happy, or to accomplish something worthwhile, or be satisfied with your life. You may not graduate first in your class, but if you can still find a good job and provide for your family then why does it matter? You may not be the most beautiful or handsome, but if you have someone you care about who loves you (Note: there’s ALWAYS someone who loves you) then why are you worried? You may not be the most famous or prestigious person in your field, but if you’re still making a positive contribution and helping those around you, why are you unsatisfied?

Unlike the society in which we find ourselves, God Himself, the Great Superlative, doesn’t demand perfection before offering us His help and love. While worldly sources tell us we’re nothing if we aren’t the best, God is constantly trying to help us see our true worth. We do strive for perfection, but He still loves sufficient: when we have been sufficiently humble (Alma 5:27), when we repent sufficiently (Alma 24:11), or when we have sufficient hope (Moroni 7:3). We don’t have to be perfectly humble, perfectly hopeful, or perfectly penitent, just sufficiently so. And when we fall short, His grace is sufficient (Moroni 10:32).

We live in a world driven by superlative impulses. We are pressured to be perfect, to have as much as we possibly can; our egos demand more, and are never satisfied with what we already have. Enough is never enough. But it’s time for a resurgence of sufficiency. It’s time we begin to accept what is sufficient for our needs, acknowledging the good we have and the good we are. We can’t be superlative in every aspect of our life, and the drive for more and the unyielding demands of perfection cause only misery. Though we strive constantly and unwaveringly for excellence, sometimes it’s ok to have, to do, or to be, sufficient.

Selfy

Human self-interest is one of the axioms of the behavioral sciences: It is at the core of economics (we all want stuff so we can live more comfortably), psychobiology (we all want to Marvin Gaye and get it on so we can pass on our genes), and more (we’re all just really obsessed with ourselves).

This of itself is not a bad thing; we don’t blame anyone for wanting to escape poverty, find a spouse/significant other, or otherwise improve their life. It’s only when these desires are taken to extremes, or when they begin to infringe negatively on the lives of others, that we view self-interest as a bad thing: a billionaire who still wants more, a leader who exploits workers for personal gain, or someone who sleeps with as many people as possible just for the thrill.

There are a variety of words in the English language that can be used to describe this kind of behavior, but two that I want to focus on that are used regularly are selfish and self-centered. Often these are conflated and used interchangeably, but a selfish person can be very different than a self-centered one (a selfie, interestingly, is not a person or a trait, though some find it to be equally undesirable).

C.S. Lewis put it well (as he usually does) when he said:

“Selfish, not self-centered… The distinction is not unimportant. One of the happiest men and most pleasing companions I have ever known was intensely selfish. On the other hand I have known people capable of real sacrifice whose lives were nevertheless a misery to themselves and to others, because self-concern and self-pity filled all their thoughts. Either condition will destroy the soul in the end. But till the end, give me the man who takes the best of everything (even at my expense) and then talks of other things, rather than the man who serves me and talks of himself, and whose very kindness are a continual reproach, a continual demand for pity, gratitude, and admiration.”

Selfishness is an intensification of our natural tendency toward self-interest; self-interest in the sense that we want to have the highest possible standard of living, the most pleasure, or the greatest happiness we can. Selfish people will often go to great, immoral lengths to increase their own status, wealth, or comfort.

Self-centeredness, on the other hand, is an intensification of our natural tendency toward self-interest; self-interest in the sense that we are very very interested in ourselves: our own story, our own personality, our own preferences, actions, experiences, etc. Self-centered people can talk about themselves for ages without ever getting bored (while the ones they speak to only last a few minutes).

Most people recognize that both traits are rather unfortunate and should be eradicated from our temperaments, but selfishness seems to be viewed as the greater of the two evils. As such, people might feel satisfied in their own selflessness (or at least, lack of selfishness), and proceed to wax eloquent of their own goodness, charity, sacrifice, and virtue, dodging one vice while unwittingly diving into another. This is what Jesus refers to when he warns against sounding a trumpet when we do good (Matthew 6:1-2). Avoiding selfishness is admirable, but once we have we must be careful not to be too prideful in our own goodness. Like C.S. Lewis said, the one who does good but speaks only of themselves can be more taxing than the one who taxes everything and speaks of others.

Because we think selfishness is worse, we are less averse to letting self-centeredness silently creep in and take its place. We must, however, guard against both equally. Selfish people are undesirable, but self-centered people are insufferable.

Ragamuffins

Note: This is a talk I gave in church in December 2019. It was significantly based in Brennan Manning’s book “The Ragamuffin Gospel” and contains several quotes from it. I’ve made some minor adjustments so as to better fit an online format, as well as some minor adjustments in wording and grammar, but it is otherwise untouched and retains it’s original tone and message.

I feel impressed to speak today about God’s love and grace, topics that feel impossible to cover in any depth or range that does justice to their power and scope. I especially feel inadequate to this task, and as such I plead for the Holy Ghost to be present.

I have been studying, reading, praying about this topic for a while now, and I feel I only have a small understanding of the depth and breadth of Father’s love for us. I absolutely do not fully understand it, and my whole life I have struggled to feel it, but I’m working on it, and I have learned and had experiences recently that have helped me to know that it is real, and it is strong, and it is often not at all what I expect it to be.

Jeffrey R. Holland said, “the first great commandment of all eternity is to love God with all of our heart, might, mind, and strength—that’s the first great commandment. But the first great truth of all eternity is that God loves us with all of His heart, might, mind, and strength.”

Do we believe that? Do we trust in it? In my experience, I have often felt it’s very true. For other people. I think, “I know He loves everyone, but how could He love ME? After all I’ve done, after I keep falling into the same sins over and over again, there’s no way.” We believe that we are unworthy of God’s love until we can fix our mistakes by ourselves, and then He will accept us.

That is wrong.

Christ says to us:

“Come now. Don’t wait until you get your act cleaned up and your head on straight. Don’t delay until you rescue your reputation, until you’re free of pride and lust, of jealousy and self-hatred. Come to Me now in your brokenness and sinfulness. Come now, with all your fears and insecurities. I will love you just the way you are–just the way you are, not the way you think you should be.” (Brennan Manning, The Ragamuffin Gospel)

Our confusion and disbelief that God still loves us even when we sin shows that we misunderstand the reason He loves us in the first place; He does not love us because we are good, He loves us because we are His.

Consider the parable of the Prodigal Son. The son went and spent his inheritance on riotous living, doing who knows what with goodness knows who. And then after losing everything and living in destitution, he decides to go back to his father. He plans what he’s going to say, preparing his speech, and is ready to accept the lowest position in his father’s house, but when he returns, his father sees him from afar and runs to him. His father doesn’t even care what he’s done; he doesn’t ask. He doesn’t even give his son a chance to give his speech and apologize. The father runs to him and embraces him and kisses him.

So it is with us. God and Christ run to us. They are not concerned with what we’ve done or who we were. They care only that we have turned to them and desire to be good.

As Ronald A. Rasband said, “God does not really care who you were and what you did. He cares who you are, what you are doing, and who you are becoming.”

As Brennan Manning said, “God wants us back even more than we could possibly want to be back.” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

This is so much easier to say than to do. Brennan Manning also said, “For those who feel their lives are a grave disappointment to God, it requires enormous trust and reckless, raging [faith] to accept that the love of Christ knows no shadow of alteration or change” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

I struggle with this constantly. My mind often drifts to the sins and mistakes I can’t seem to overcome, the things that I keep doing over and over, and I feel that disappointment. I ‘know’ God loves me, but I can’t believe it because of all the things I’ve done. That’s when I really experience that need for reckless, raging faith. The active, concentrated belief that He loves me even when I don’t love myself.

It’s hard. Good gracious it’s hard. But it’s true; He loves you even when you don’t love yourself.

Reverend John Claypool said, “We all have shadows and skeletons in our backgrounds. But listen, there is something bigger in this world than we are and that something bigger is full of grace and mercy, patience and ingenuity. The moment the focus of your life shifts from your badness to His goodness and the question becomes not ‘what have I done?’ but ‘What can He do?’ Release from remorse can happen.” (As quoted in The Ragamuffin Gospel)

It is true that God still ‘cannot look upon sin with the least degree of allowance’ (D&C 1:31), but that doesn’t mean that when we come before Him dirty from sin that He is disgusted by our presence, sending us off to try to clean ourselves up before He accepts us. Instead, He sees that we are dirty from head to toe and helps us clean up; He anoints our head and smiles up at us as He washes our feet. We mustn’t think that we must repent on our own. It is impossible, and He wants to help us.

In stake conference President Stacy Peterson said, “Forgiveness isn’t repentance. The goal isn’t forgiveness, the goal is change.”

It has also been said that, “Repentance isn’t what we do to earn forgiveness, it is what we do because we have been forgiven.” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

Christ is already there offering us forgiveness, offering us His grace. We just have to accept it.

Now you might think, yeah I know that’s what I have to do, but how do I do it? How do I access God’s grace and allow it to change me?

The first step to accessing God’s grace in our lives, even before the basic primary answers (read the scriptures, pray, and go to church), is to be honest.

The writer Walter Anderon said, “Our lives improve only when we take chances–and the first and most difficult risk we can take is to be honest with ourselves.” And, I would add, honest with God.

It may seem obvious, but there is no point in trying to hide who we are from God. Yet sometimes that’s exactly what we do. That’s what I’ve done. I become aware of some aspect of myself that I hate, and I don’t want God to think that that’s the kind of person I am, so I never bring it up. I pretend it’s not there. I pretend that, while not perfect, I don’t do things that are that bad.

But we don’t have to hide from God. We don’t have to pretend we’re something we’re not, or pretend we’re not something we are. Elder Gerrit W. Gong said, “Remember, he knows all the things we don’t want anyone else to know about us–and love us still.” God meets us wherever we may be; he reaches down as far as we have fallen, then lifts us back up.

Brennan Manning said, “To live by grace is to acknowledge my whole life story, the light side and the dark. In admitting my shadow side, I learn who I am and what God’s grace means.” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

Grace enters our lives proportionally to how honest we are with God and with ourselves. We must bring ourselves, our WHOLE selves, to God, the good and the bad, the beautiful and the ugly, and lay it at His feet.

“The Good News means we can stop lying to ourselves. The sweet sound of amazing grace saves us the necessity of self-deception, It keeps us from denying that though Christ was victorious, the battle with lust, greed, and pride still rages within us. …When I go to church I can leave my white hat at home and admit I have failed. God not only loves me as I am, but also knows me as I am. Because of this I don’t need to apply spiritual cosmetics to make myself presentable to Him. I can accept ownership of my poverty and powerlessness and neediness.” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

“God expects more failure from you than you expect from yourself.” (The Ragamuffin Gospel)

If you feel like you are struggling to feel God’s love, or that you have been left alone to try and sort out the pieces of your broken life alone, I urge you to talk to God. Tell Him how you feel. Be honest with Him and say the things you wish you could say to your friends and family. Too often we feel like He is a distant being, an uninterested dealer of justice alone. Not so. He is here, full of mercy, knocking at our door, waiting for us to open up to Him. His is not a passive or a distant love, it is active, immediate, and accessible. We just need to turn to Him.

The Rest is History

Of all the academic subjects in the world, none seems to have the reputation for boredom and pointlessness quite like history (mathematics gives it a run for its money, but you can at least see the importance of maths in building a bridge, or when you have 62 watermelons and you give 13 to Jimmy and you want to know how many watermelons you have left). History, it seems to many, has no good answer to “When are we ever going to use this?” aside from the (in)famous rebuttal “those who fail to learn from the past are doomed to repeat it” (or one of its many variations).

I love history (generally), and I voluntarily read all sorts of things to learn it, but I understand why some people don’t share my enthusiasm. I’ve realized, however, that when someone says, “I hate history” they’re putting some serious limits on the things they don’t hate. Let me explain.

We tend to view history as one of the many subjects available for study, alongside maths, music, engineering, basket-weaving, etc. etc. etc. While this is a useful way to delineate subjects and topics, the reality is that the study of any subject is, in large part, history.

Take politics for example: in order to be an effective politician, you must have a thorough knowledge of what has happened in a nation or region’s past, who its enemies are, what kind of internal conflict has occurred, what laws are already in place, who not to mess with, who you can definitely mess with, and so on (this is generally what is taught in “history” classes).

To be an engineer you learn about Newton, Einstein, Maxwell, and a host of other influential figures, as well as past structures, inventions, and/or developments in the field.

To be a musician you learn and perform historical pieces of music, learn about the various styles, instruments, and influences of different time periods, not to mention the composers and performers of those times.

The examples go on and on with nearly every subject, and even though most subjects aren’t solely history, it’s easy to see why learning the history of a subject is vital for an adequate understanding that subject (If you have any examples of subjects in which you don’t need to learn any history, I’d love to hear them). Learning history doesn’t even stop with professional or academic pursuits; we develop our friendships and relationships in large part by learning (and participating in) the histories of those around us. We can’t even understand ourselves if we don’t understand our own personal history.

We are what we are, we know what we know, and we do what we do because of history. Each moment has been shaped by the events that preceded it; if we don’t understand the past, we don’t understand the present. Without understanding the present, we are unprepared for the future. As Maya Angelou said: “If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.”

Overall, even though some might hate it and many fail to see the value of learning it, history, in all its forms, is one of the most important subjects for us to learn. Without a knowledge of the past, we really are doomed to repeat it: in engineering, art, and our own lives.

One last thought, as a corollary to what I’ve said so far: though history is vitally important to learn, we mustn’t get caught up in it. We learn history not to dwell on the mistakes of the past or to lament the conditions of the present; we learn history so we can learn from those mistakes and better shape our future. The second part of the quote from Maya Angelou is this: “I have respect for the past, but I’m a person of the moment. I’m here, and I do my best to be completely centered at the place I’m at, then I go forward to the next place.”

We don’t make or fail to make history. The sands of time flow regardless of the actions we take, and history is made whether we like it or not. We only have to decide what our place in it will be.