In my last post I introduced the concept of affordances and their bearing upon creativity, explaining why affordances are a core ingredient in most creative endeavors. In this post, I’ll be taking it a step further and exploring the effects of affordances on the more concrete yet closely-related field of design.

For designers, telling them that affordances are an important aspect of design is like telling someone that the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell: they already know it, and they will remember it until the sun burns up and envelopes the earth in it’s warm embrace (at least based on what my designer friend told me. Maybe not in those exact words though). For us non-designer laypeople, the applications of affordances in design are rather more obscure (at least based on my own experiences). No matter who you are, however, affordances are an important aspect of design.

For much of human history, the only design that went into the objects around us was the design of nature; if you wanted a nice sharp stick for throwing at the animals you wanted to eat, you had to go find a stick that just happened to grow that way. If you wanted a nice place to build a nest to sleep in, you had to go find a tree that just happened to have what you were looking for. As human technology advanced, more and more objects were designed not by nature but by humans themselves. Now, as I write this, the only thing in this room that wasn’t designed by a human is my own body. Design plays an astonishingly large role in our lives, but most of the time we don’t even notice it.

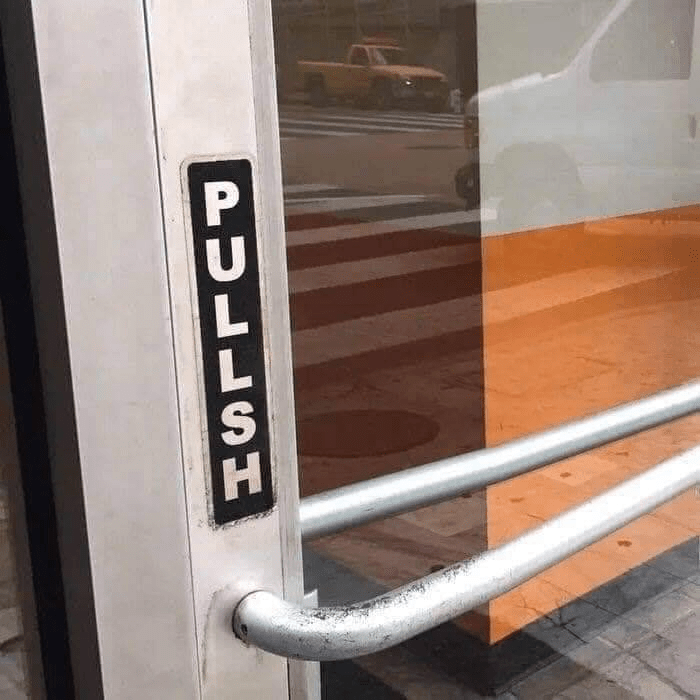

Counterintuitively, the not noticing is actually an indicator of good design; generally, the more aware we are of how something has been designed, the poorer is the design (or the more involved in the design process you are, but that’s cheating). Just take a look at these and you’ll see what I mean.

So how does this connect to affordances?

The use of any product is dictated by the affordances of the user. The more intuitively the affordances are assigned, the more effective is the product. This is the domain of design, and is the reason good design is nearly unnoticeable: when something is well designed, it’s so easy to use we don’t have to think about it.

So how does one make such intuitive design?

It’s important to realize that while the use of a product is dictated by the user’s affordances, the design of the product guides those affordances. Certain features can trigger almost automatic responses: buttons are for pushing, switches are for flipping, handles are for holding or carrying or pulling. These automatic responses are what make good design invisible, and good design utilizes these features to guide the user.

Don Norman, in his book The Design of Everyday Things, takes issue with such flippant invocations of affordances, especially in the digital realm. His position is that because every touchscreen already affords all the possible combinations of touches and swipes, any indicators (like arrows or Xs or buttons) aren’t about affordances but rather signifiers (something that explicitly directs a user how to use something). And while Don Norman is a professional with years of experience in his field, I am a college student writing a blog, so I say that he’s wrong.

…

Ok perhaps he’s right, but while it’s true that touchscreens do already afford touching and swiping and all those things, it is also true that literally everything around us affords those things too, so it’s a bit silly to me to say that buttons and scroll bars and switches aren’t affordance-based because “touching is already an affordance”. But I suppose I can be humble enough to agree to disagree. (In reality, Norman is very experienced and he has some fascinating things to say about design and affordances and signifiers.)

Because affordances (ok fine, and signifiers) play such a role in design and user experience, it is important not to design something to look like a button or switch or handle when it doesn’t actually work that way. This is common in digital design, where it can be very easy (and very frustrating) to confuse button-like animations for actual buttons, leading the user to relentlessly tap or click without realizing they aren’t buttons at all.

Like this.

Interestingly, this is one of the main strategies when it comes to clickbait and other garbage, where deceiving the user with such features leads to more clicks, visits, and revenue. Even just having an improperly-sized hitbox for buttons can be maddening for the user but a gold mine for the developer (I’m looking at you, pop-up ads). As a famous general once said, “It’s a trap!”

And this is where I’ll finish for now. I could keep going, but literal volumes have already been written, both with pen and pixel, about this topic, and there’s no way I could cover all the interesting examples and principles that exist. I just want to emphasize that affordances (and signifiers) play an enormous role in our lives without us even realizing it. They affect our homes and our jobs and our schools; they affect the ways we create and consume; and as we’ll see in my next post, they even affect the ways we interact with others.

But that’s for next time. For now, don’t let the door hit you on the way out:

One thought on “You Can Design It”