“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

H.P. Lovecraft

“We fear things in proportion to our ignorance of them”

Christian Nestell Bovee

We humans, in spite of all our rhetoric about being logical, rational creatures, are constantly at the mercy of, or significantly affected by, our emotions. They affect how we respond to and interact with others, how we spend our time, what (or if) we eat, and nearly all other decisions we make. The stronger the emotion, the greater its effect in our life, and one of the strongest (and therefore most influential) emotions we experience is fear.

Fear, like all emotions, plays an interesting and complex role in our existence as biological organisms. Clearly it evolved for an important life-saving purpose: being afraid of snakes and spiders makes you less likely to get near one, and therefore less likely to die by being bitten. Being afraid of bears makes you less likely to fight one, making you less likely to get suplexed.

On the other hand, fear can be one of the most crippling emotions we experience. The fear of being judged, ridiculed, or humiliated prevents people from expressing themselves and opening to others. The fear of failure prevents people from starting new projects, exploring alternate career paths, or developing relationships. Fear of dogs prevents people from enjoying dogs. In each of these cases, fear limits the human experience and inhibits the satisfaction that comes from effort, accomplishment, and connection (and dogs).

So what exactly is fear?

It seems like a stupid question because, duh, everyone knows what fear is (except for those rare people who lack functional amygdalae), but if you really tried to answer it right now I imagine many of you would say, as I first did, something like: “it’s, uh… being afraid of something.”

Everyone knows what fear feels like, but not necessarily what it is. It’s one of those fundamental experiences that is hard to describe precisely because it’s fundamental (similar to describing what salt tastes like, or what blue looks like).

What fear is, however, differs from what it feels like, just as what blue is differs from how it is perceived.

So what exactly is fear?

While my thoughts may not be a complete (or even adequate) exploration into the nature of fear, they have changed my own perspective on fear, and how to deal with it more effectively. As I’ve thought about and experienced fear (and then thought about my experiences), I’ve come to three conclusions:

Conclusion One: Fear is Uncertainty

Fear is a predictive emotion. It is based on our analysis of the future, and what we think could happen, not necessarily on what will happen. We don’t fear the past or the present, because we know what they hold, but we do fear their possible impact on the future. And we fear the future because we don’t know it. Take, for example, a fear of flying: when someone is afraid of flying, what they’re actually afraid of (usually) is that the plane might crash, a possible, though perhaps not probable, outcome. Or perhaps someone fears heights: what they are really afraid of isn’t being up high, it’s the uncertainty of whether or not they will fall.

So it is with all fears: we fear the uncertainty of the future, and it’s innumerable possibilities.

(An important, perhaps obvious, note: The actual probabilities of an event occurring are not always directly proportional to the fear experienced; Rather, our perception of danger is what drives fear. Phobias and anxiety disorders are caused by a perception that is disproportionate to the actual probability of an event. This is the distinguishing factor between a healthy and an unhealthy fear: a healthy fear is one in which our perception of danger and our response to it are proportional to the actual danger and probability of an event. An unhealthy fear is one in which our perception and/or response are disproportionate to the actual danger present. This can go both ways, either as an overreaction to uncertainty or as an underreaction to uncertainty, though the latter is often, erroneously, called courage and as such is often, erroneously, encouraged.)

Corollary: When an outcome is certain to occur, we no longer fear it.

This may seem counterintuitive, but it’s true. When we know something is going to happen our fear shifts from the uncertainty of the event to the uncertainty of it’s outcome. When the uncertainty of an event is removed entirely, so too is our fear. Often what we consider to be fear is really an aversion to something (perhaps because it was associated with fear in the past). You can see this in any fear you have. For example, when I say I’m afraid of needles, what I really mean is that 1) I’m afraid what it would be like if a needle broke inside my arm and 2) that I actually hate them, because they hurt.

Or take my previous example of a plane crashing: if we are in a plane and we know with certainty it’s going to crash, we lose our fear of the plane crashing and instead begin to fear that being in a plane crash is going to be a horrible experience (which seems like perhaps a reasonable expectation). Interestingly, the whole reason we would experience the fear of a plane crash in the first place is because it leads naturally into our secondary fear of what a plane crash will be like. This leads me to my second conclusion.

Conclusion Two: Fear is Layered

Fears are like ogres, which, in turn, are like onions (or cakes or parfaits): they’re layered. Nearly every fear we have is built upon a different fear one layer below it, a fear that can be revealed by asking the question: Why?

For example: You’re afraid of the ocean. Why are you afraid of the ocean? Because you don’t know what you’ll encounter in it. Why are you afraid of what you might encounter? Because it might eat or sting or bite or drown you. Why are you afraid of being eaten, stung, bitten, or drowned? Well, hopefully that answer is rather obvious.

This exercise can be performed with any fear, often to great, enlightening effect. You may find fears you didn’t realize you had, or you might find that the things you thought you feared weren’t worth fearing. Whatever it is, remember: Fears rarely exist in isolation.

Eventually, however, you will reach a point at which asking “why?” doesn’t lead you any further. This leads to my third and final conclusion about fear.

Conclusion Three: Pain is the Root of Fear

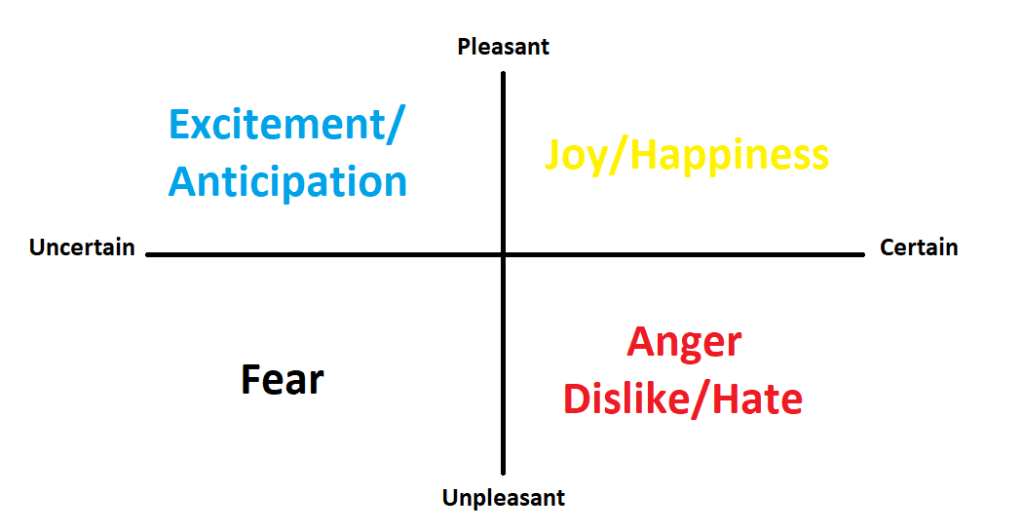

When we follow any fear to it’s fundamental source, we arrive at pain. Pain is the root of all fear. If it isn’t painful, emotionally, mentally, or physically, we don’t fear it, even if it is full of uncertainty. This is what separates fear from excitement or anticipation: we are excited for pleasant uncertainties, but fear unpleasant ones.

This is not to say that any time we expect to experience pain or discomfort we experience fear, but rather any time fear is present it is because of pain or discomfort. Social anxiety is caused by fearing the pain of ostracism or loneliness. We fear the pain of rejection, the pain of shame, or the pain of living without a loved one. Whatever it is we fear, it is because we fear pain.

Conclusion

With these conclusions taken together, we arrive at our (partial) definition of fear: It is an unpleasant emotion we experience when faced with the possibility of pain. If it is not uncertain, it is dislike or hatred. If it is not painful, it is excitement or anticipation. If it is neither, then it’s enjoyment or happiness. This is illustrated in this very simplistic chart I’ve made (Obviously not every emotion is represented on this chart, like disgust or guilt or hunger, and often these emotions can blend with each other, but this serves my present purposes):

The first step to overcoming any obstacle is to understand what the obstacle is; “Know thy enemy”, as Sun Tzu admonished. With our improved understanding of what fear is, we are more prepared to learn how to overcome it. And as George Addair said: “Everything you’ve ever wanted is on the other side of fear.”